Introduction

Imagine a world where food was never guaranteed. For tens of thousands of years, humans lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers, constantly moving with the seasons. Then, around 10,000 BCE, the Neolithic Revolution changed everything. This wasn’t a sudden shift, but a gradual transformation in which humans began to domesticate plants and animals, transitioning from foraging to agriculture and settled life. The change started in the Fertile Crescent and spread across the globe, with rice in China, maize in Mesoamerica, and millet in Africa.

This transformation wasn’t just about food production—it was about control over resources. With agriculture came permanent settlements, specialization of labor, and the creation of social hierarchies. Populations grew, and surplus food allowed for technological innovation, the rise of cities, and eventually, the development of class-based societies.

In essence, the Neolithic Revolution was the beginning of human domination over nature, fundamentally altering how people related to land, labor, and each other. This slow, irreversible change set the stage for the rise of complex societies, laying the groundwork for the modern world.

Life Before the Neolithic Revolution

Before the Neolithic Revolution, humans lived as hunter-gatherers, relying on nature for food and survival. They led a nomadic life, moving in small groups to follow seasonal food sources like wild animals, fruits, nuts, and roots. Without permanent homes, they built temporary shelters from natural materials and carried only essential tools. Their lives revolved around immediate needs—there was no food storage or surplus. Despite their simplicity, these communities used well-crafted stone tools and had mastered fire, which was crucial for cooking and protection. Socially, they were cooperative and close-knit, with early signs of art, rituals, and belief systems seen in cave paintings and burials. While effective for survival, this lifestyle limited population growth and long-term stability, setting the stage for the revolutionary shift to agriculture.

Causes of the Neolithic Revolution

The shift to agriculture was deeply rooted in changing material conditions and the practical needs of early human communities. As the Ice Age ended, a warmer and more predictable climate allowed plants to grow more consistently, while the decline of large wild animals made hunting less dependable. With growing populations and greater pressure on natural resources, communities could no longer rely solely on foraging. In this context, people began to manipulate their environment more intentionally—observing how seeds grew, selectively gathering useful plants, and gradually domesticating animals. These developments allowed some groups to produce more food than they immediately needed, giving rise to food surpluses. Over time, this surplus began to reshape human relationships. Those who controlled land or resources could gradually gain more influence, leading to new divisions of labor and inequality. What began as a practical response to survival challenges would eventually lay the foundation for structured societies, economic hierarchies, and systems of control over both people and nature.

Birth of Agriculture

As communities deepened their interaction with the land, they began actively shaping the natural world to meet their needs. In various regions, people gradually domesticated specific plants that proved most reliable and nutritious—wheat, barley, and lentils in the Fertile Crescent; rice in East Asia; maize in Mesoamerica; and millet and sorghum in parts of Africa. This process wasn’t sudden but emerged through generations of observation, trial, and adaptation. Similarly, animals were brought under human control—not just for meat, but for milk, labor, and later, social status. The domestication of dogs came first, followed by livestock such as sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs. As food production became more systematic, people developed new techniques to maximize yield: slash-and-burn cleared land for planting; irrigation redirected water to crops; and plowing made soil more fertile and manageable. These innovations marked a deeper shift—humans were no longer just responding to nature, but increasingly organizing it around their labor, setting in motion new relationships with land, resources, and each other.

Permanent Settlements and Village Life

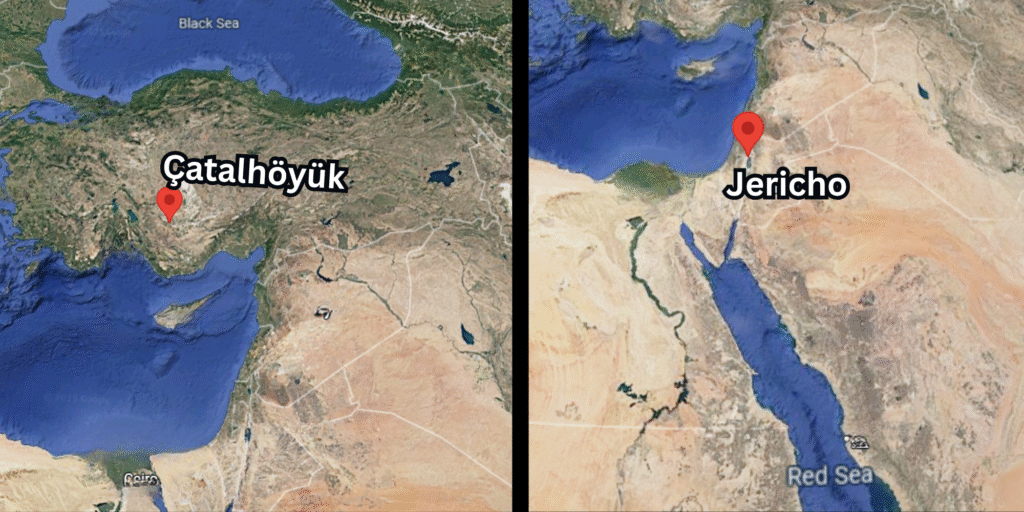

As food production stabilized, people no longer needed to move constantly in search of sustenance. This shift led to the rise of permanent settlements, some of the earliest being Jericho in the Levant and Çatalhöyük in Anatolia—sites that show clear evidence of long-term habitation. These were not just clusters of houses but organized communities with mud-brick homes, food storage facilities, and shared spaces for daily life. The move from temporary camps to permanent dwellings reflected deeper changes in how people related to land and labor. With fixed homes came new concerns: protecting surplus food, maintaining tools, raising children, and coordinating group effort. Communal life became more structured, and the built environment itself—walls, pathways, storage rooms—mirrored the emerging social order. In settling down, humans were not simply changing where they lived; they were laying the groundwork for new forms of cooperation, dependency, and eventually, control over both resources and social roles.

Social and Economic Changes

The ability to produce surplus food allowed populations to grow, fundamentally altering the structure of society. With more reliable food supplies, communities expanded and became more complex. This surplus also gave rise to a division of labor: some people focused on farming, while others became artisans, crafting tools, pottery, and textiles. Leaders emerged to manage resources and make decisions, marking the early signs of political organization. As people accumulated more goods, private property began to take form, creating distinctions between those with access to land and wealth and those without. This shift also led to the rise of social hierarchies, where power, wealth, and status were increasingly tied to ownership and control over resources. Furthermore, as surplus goods were produced, trade and barter systems developed, enabling communities to exchange goods, ideas, and technologies, laying the groundwork for more extensive networks of interaction and economic growth.

Technological and Cultural Advancements

As agricultural societies grew, so did their need for better tools and technologies. Polished stone axes made clearing land for farming easier, while sickles and grinding stones allowed for more efficient harvesting and processing of crops. Pottery emerged as an essential tool for storage and cooking, providing durable containers for both food and water. The weaving of textiles from plant fibers became another critical innovation, supporting both clothing and the growing demand for trade goods. Alongside these practical advancements, early human societies also began developing religious practices and burial rituals, marking a shift toward symbolic thinking. These rituals helped reinforce social bonds and reflect a growing concern with life beyond immediate survival, indicating that humans were not just adapting to the material world but also beginning to shape their cultural and spiritual lives.

Environmental Impact

With the rise of agriculture, the human impact on the environment became more profound. Deforestation accelerated as forests were cleared for farming, leading to soil depletion as overworked land lost its fertility. The introduction of domesticated animals, such as cattle and sheep, further altered landscapes, as grazing and trampling compacted the soil and reduced plant diversity. This shift marked a dramatic increase in human control over nature, as people not only cultivated crops but also shaped their surroundings to meet their growing needs. However, this newfound control came with consequences, as the ecosystems that had once supported hunter-gatherer life began to transform under human influence, laying the foundation for the environmental challenges we face today.

Regional Variations

As agriculture spread, distinct independent agricultural centers emerged across the world, each developing its own methods and innovations. In the Fertile Crescent (Southwest Asia), early civilizations cultivated wheat and barley, laying the groundwork for complex societies. The Nile Valley in Africa benefited from the predictable flooding of the Nile, allowing for rich, irrigated fields of crops like wheat and flax. In the Indus Valley (South Asia), the domestication of crops like barley and wheat, along with advancements in urban planning, marked a shift towards organized civilizations. Similarly, the Yellow River region in China saw the rise of rice and millet farming, leading to the establishment of one of the world’s earliest dynasties. On the American continents, Mesoamerica and the Andes independently cultivated maize, beans, and potatoes, building societies with distinct agricultural practices. These centers not only shared the development of agriculture but also became the foundations for diverse civilizations, each adapting agriculture to their unique environments.

Legacy and Long-Term Impact

The rise of agriculture created the conditions for the development of complex societies. With the ability to produce surplus food, communities could support larger populations and specialize in different tasks, leading to the emergence of cities as centers of trade, culture, and governance. This surplus also allowed for the development of writing systems to manage resources, keep records, and communicate across distances. Governments began to form to regulate these growing populations, enforce laws, and control land and resources. Agriculture not only supported the growth of early cities but also set the stage for the Bronze Age, where the discovery of metalworking further advanced technology and warfare. This agricultural revolution laid the foundation for the rise of complex societies, with lasting impacts on social structure, economics, and culture.

Conclusion

The Neolithic Revolution stands as one of the most significant turning points in human history. It marked the shift from a nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled agricultural societies, forever transforming human society, economy, and environment. This transformation didn’t happen overnight, but over thousands of years, as people learned to manipulate the land, domesticate animals, and create surplus food. The consequences were far-reaching—agriculture allowed for the rise of cities, writing, and governments, fundamentally altering social structures. While it was a slow process, it was irreversible, shaping the development of modern civilization and laying the foundation for the world we live in today. From the rise of complex societies to the environmental changes it brought, the Neolithic Revolution set the stage for everything that followed, from technological advancements to global trade.

📌 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

❓What is the Neolithic Revolution?

The Neolithic Revolution was the transition from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a settled agricultural one. Beginning around 10,000 BCE, humans started to domesticate plants and animals, which led to permanent settlements, surplus food production, and the rise of complex societies.

❓Why did humans shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture?

This shift was influenced by a warmer and more stable climate after the Ice Age, decreasing availability of large game animals, population growth, and the need for more reliable food sources. Agriculture allowed communities to produce surplus food, settle in one place, and develop new technologies.

❓Where did the Neolithic Revolution begin?

The Neolithic Revolution is believed to have first occurred in the Fertile Crescent (modern-day Middle East), but it also happened independently in other regions like China, India, Mesoamerica, and Africa, each domesticating their own native crops and animals.

❓What are the key crops and animals domesticated during the Neolithic period?

Early humans domesticated wheat, barley, and lentils in the Fertile Crescent; rice in East Asia; maize in Mesoamerica; and millet and sorghum in Africa. Animals like dogs, sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs were also gradually domesticated for food, labor, and companionship.

❓How did agriculture affect human settlements?

With reliable food sources, humans could build permanent homes and villages. This led to the development of early cities, like Jericho and Çatalhöyük, and changed how people organized labor, stored food, and built social relationships.

❓What were the social changes during the Neolithic Revolution?

Agriculture created food surpluses, which led to population growth, specialized labor, property ownership, and social hierarchies. Societies became more structured, with emerging leadership roles, trade systems, and divisions between the rich and poor.

❓How did technology evolve during the Neolithic period?

Neolithic societies invented and improved tools such as polished stone axes, sickles, grinding stones, and pottery. They also developed irrigation, slash-and-burn farming, plowing, and textile weaving, all of which increased agricultural productivity.